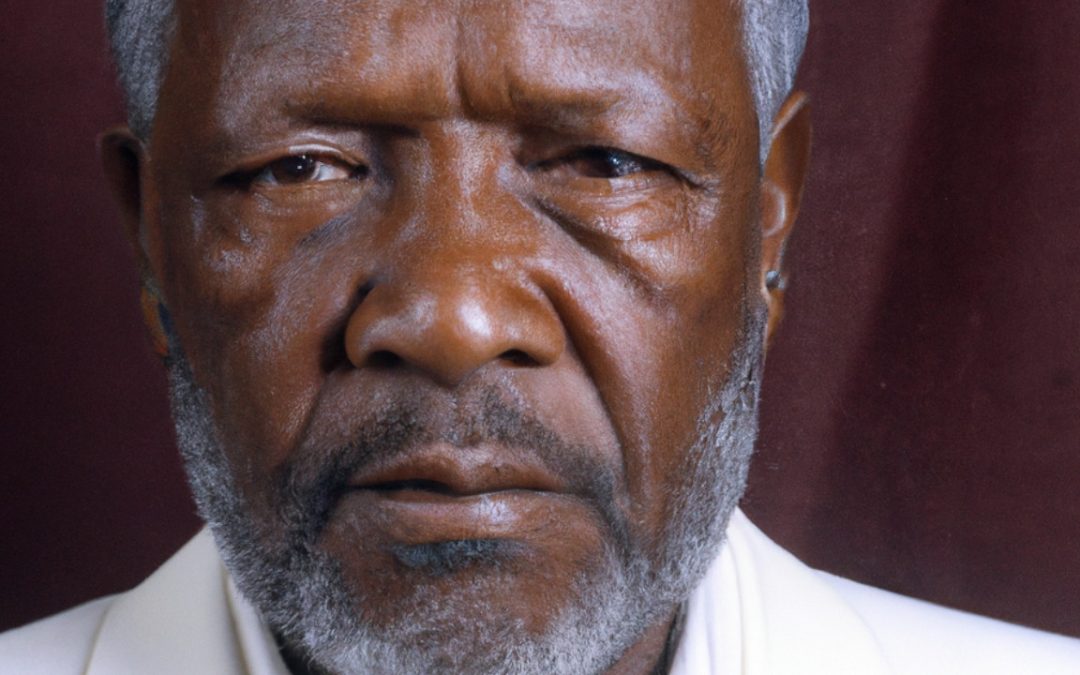

Hissene Habre is not exactly well known outside of central Africa. But in his native country of Chad, just uttering the name conjures up images of horror. For eight long years he ruled over Chad in the 1980s, during which time he was responsible for the executions of 40 thousand political dissidents. Born into a family of sheep herders, little ambition or political achievement could have been expected of someone in his circumstances. But at the time Chad was still part of the French empire, and Habre was somehow appointed to a minor position within the local French authority. There he showed the three key elements of any successful politician – loyalty, intelligence, and cunning. With this natural acuity he impressed those above him, and won a scholarship to study in Paris.

The Rise To Power

In France he earned several degrees in political science, including a doctorate, and on returning to Africa he was a transformed man. But he was different in a way you might not expect, now seeing the French as brutal colonial exploiters, rather than benevolent granters of opportunity. Not content with becoming a simple administrator in French Africa, Habre soon joined a rebel group called FROLINAT. He would not be welcome in the group for long, since he had a habit of playing various ideological factions against each other to suit his own ambition. The inevitable outcome of this was Hissene Habre joining and splitting from numerous revolutionary groups, often leaving them far more dis-unified than when he joined their cause. In 1974 he was done with debating theoretical political issues and led a small armed group to attack the town of Bardai.

It was a small scale attack aimed mainly at the taking of hostages who would later be exchanged for arms. But just four years later Habre and his supporters had become strong enough to call themselves a significant force in the Chadian political landscape. In 1978 he was given the position of Prime Minister of Chad. While much less powerful than the President, it gave Habre a new legitimacy. Popular among the military for his corruption and brutality, more soldiers came to identify with the new Prime Minister. Then late in the same year his supporters went to battle with those loyal to the President. For a moment it seemed like anyone’s fight – but then the Habre faction was driven back. Habre himself was forced to flee the country and his supporters were in big trouble.

Ruling Chad

Still, the power struggle continued on a much lower lever, with Habre forces taking hold of strategic rural strongholds. Six years later Habre was even able to return to Chad, defeating the enemy and assuming the position of president.

On taking power in 1982 he immediately took to maintaining it primarily through violence and intimidation. His political parts, The National Union for Independence and Revolution, was the sole party allowed to operate in Chad. Like other one party dictatorships, there was a widespread general policy of torture and murder. Hissene Habre changed the actual constitution of Chad to give himself and the party ultimate authority. But for some reason he still bothered to hold an election in 1990. That was his last year in office and no doubt it was a last ditch effort to lend legitimacy to the regime. As the sole legal party, they won 100 percent of the vote! Perhaps the worst crime of Habre was ethnic cleansing. Viewing certain ethnic groups as more prone to rebellion, he had members of said groups killed and arrested on a grand scale.

Thousands were made to suffer untold misery at the hands of Hissene Habre. It was the kind of brutality that could only be short lived, and as time went on his government grew ever weaker. In the late 1980s, several coup d’etat against Habre were attempted by high ranking officials. None of them were successful but their increasing frequency was an omen of death for the regime.

The Fall

Then in 1990s a large rebellion finally defeated Hissene Habre. Realizing his record in office will catch up with him, Habre fled the country. With millions of dollars of tax payer money he fled to Cameroon to seek political asylum. While the French government had until this point given some measure of support to Habre, they had now washed their hands of him. And so the international community allowed Chad to be taken over by yet another cadre of shady figures while the old one was torn apart. In time Hissene would settle in Senegal, and find some measure of protection in the Senegalese government. Like many former African dictators it was unclear if he would ever face consequences for his past. But over the years more detail emerged, showing the true scope of his crimes.

Accused of killing 40 thousand people, and allowing the rape and torture of countless more, many demanded he stand trial. But the Senegalese government was reluctant to extradite him, denying requests by Chad, Belgium, the European Union and the African Union. In 2008, a court in Chad held a trial without Habre and sentenced him to death. Yet he remained in Senegal a free man. Then in 2016 Senegalese authorities finally bowed to the pressure. A special co-operative tribunal was set up between the African Union and Senegal, which found Habre guilty for war crimes. Specifically, he was found guilty of rape, slavery and unlawful killing. Hissene Habre has since been in prison.