Norodom Sihanouk has the unique distinction of being a king turned dictator turned exile turned nationalist activist turned king in a restored monarchy. Through the years he was witness to multiple wars and seems to have lived multiple lives. Just one of such was that of a prolific film producer and occasional actor. Despite this, he is not an especially well known figure outside of his native Cambodia. Why? Because the infamy of his political rivals happens to eclipse his own. But the life and times of Norodom Sihanouk is a story that needs to be told. One which must be known to all wishing to understand the chaos of modern Cambodia.

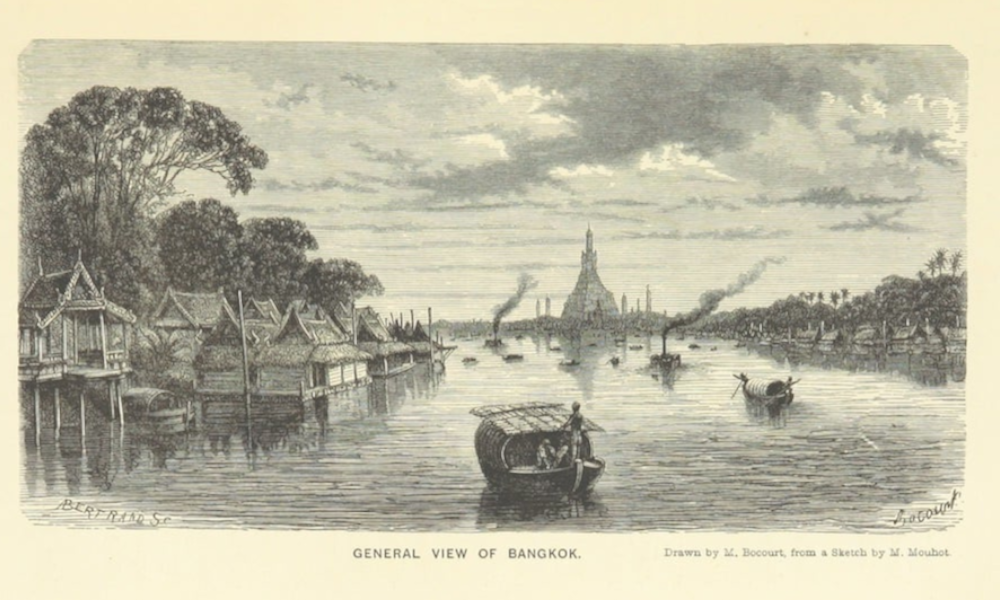

Few today can image what it was like. To be born into a vassal state, a neglected backwater of empire at a time when empire was an uncontested fact of life. Cambodia is the backwater I speak of. Since 1863 it had been dominated by France, the Cambodian king signing a deal that gradually drew it into their colonial empire. The French Protectorate of Cambodia, a Kingdom within a republic. Yet the kingdom was small and poor, leading to Cambodians paying a higher tax rate than residents of other French Indochina territories. Not even the king was a free man. Rather, he was a French subject. They all were, and nobody quite knew what to think of that.

Norodom Sihanouk was brought into a such a world, being born in Phnom Penh in 1922. Unlike most future dictators, he was born in the purple. What I mean is that his mother was a princess. Her father was the current king of Cambodia, which is less impressive than it sounds, the monarchy was little more than a puppet reigning at the pleasure of the French Empire. Still, it meant that she, and her progeny had it better than most. As a member of the royal family, Norodom Sihanouk was afforded the best education money could buy, within French Indochina at least. There was some possibility of politics waiting in his future, many high ranking governmental figures having royal blood at the time, but his main interest was in sport. Then during the tail end of his teenage years, his career was chosen for him.

An Unlikely King

It was 1941 and his kingly grandfather passed away. As with every monarchy, attention immediately turned to the question of succession. The king was dead, and now the throne longed for another. But who would it be? First in line was Sihanouk’s uncle Sisowath Monireth, who naturally expected to be named king without objection. But he was hard headed. Not in a good way. So after brief deliberation it was decided by the French governor that the crown should skip a generation, passing instead to his nephew Norodom Sihanouk. So at the naive age of 19, Sihanouk was crowned king of Cambodia. Chosen for his passivity, the young king dedicated his time to hobbies. To soccer and amateur film production. That is, after all, why the French picked him.

But going into the second world war, France soon lost control of the region. Japanese soldiers swept into Cambodia like a bloody red wave, crushing all who opposed them and driving European administrations into the sea. And so the fate of his nation now genuinely relied on the actions of Norodom Sihanouk. For the most part they were happy to let things continue as they were, at least in name. French Indochina would carry on operating as if it were a French colony, despite clearly being occupied the Japanese military. But as world war two bled into it’s final year, the Japanese began to buckle under the strain of limited resources. In desperation, they pressured Sihanouk to officially break from the French Empire. Never one to disobey orders, he swiftly complied. In hist defense he had little choice, but it was still a seismic shift for Cambodia.

He declared independence from France and assumed the position of Prime Minister. Nationalist forces within Cambodia were not happy though, overthrowing and replacing Sihanouk with a republican prime minister. It was all very hectic, and it got more hectic still when French forces returned to Asia.

Japan was eventually beaten back and pale faces once again marched the streets of Phnom Penh. They carried out a coup of their own, replacing the nationalist prime minister with Sisowath Monireth, the uncle leap-frogged by Sihanouk years before. But Sihanouk remained King of Cambodia. France realized that their Asian colonies would need concessions if they were to remain French, and decided the king should be allowed to remain in place for the sake of stability. In the case of Cambodia, a series of reforms were signed into law. First of all, it was to be an autonomous state within the French Union, giving Cambodia much more freedom as a whole. And Sihanouk also spread individual freedom, establishing an elected legislature and guaranteeing freedom of the press. And that’s not all. Following years would see him repeatedly reopen negotiations in the hope of gaining more autonomy for Cambodia.

But it wasn’t all plain sailing. By 1949 he was tired of the political infighting that always comes with democracy. So like Charles the first of England he dissolved the legislature and began issuing decrees. It continued this way for two years, the kingdom running on his command like a medieval state. Believe it or not, the people of his kingdom were not all too pleased about this. A well intentioned tyrant remains a tyrant nonetheless, and so massive opposition to the king spread. Said opposition was especially concentrated in the countryside, where it took on a republican, anti-colonial, and often communist nature. That’s how an ancient monarchy becomes divided along such radical lines.

Elections were held in 1952, but by the year’s end he’d dismissed the prime minister and again taken over the role himself. This prompted nearly as many anti-monarchy protests as anti-French ones. So in a desperate attempt to win over the public, he aimed to gain full independence from France. If able to convince the French to let Cambodia go, it might just be enough to cleanse him of all past mistake. Possibly enough to save the very institution of monarchy itself. So to Paris he traveled on a diplomatic mission, and to Canada and the US to publicly argue for the Cambodian cause. He argued that, as a traditional monarchy, an independent Cambodia would be an important ally of the capitalist west, who even in those days feared the spread of communism in South-East Asia.

Then, back on the streets of Cambodia he held mass demonstrations against colonial rule, projecting him as the only safe alternative to both colonialism and communism. The plan worked, and over time France granted more and more powers to the small Asian state. Then in October of 1953 the French government conceded defeat. Come November and it was announced. And it could not have come at a more crucial time. With the wars in Korea and Vietnam winding down – at least for the moment – making Cambodia a vital strategic partner in keeping the peace. No doubt this was a key reason France so readily reversed course on the issue of Cambodian independence. As such, financial and diplomatic support flooded into the young nation. Sihanouk made discriminative use of such support to bolster his ever growing political influence domestically. In theory Cambodia was a democracy, but in practice not so much.

A New Kind of Ruler

Elections were far from being free and fair. In fact, they were merely a formality. And as time went on the irrelevant elections grew ever less relevant. The awkward potion facing Cambodia is that her king was simply not satisfied being a normal king, believe it or not. This was not a man content to be but a constitutional monarch. He was born leader of men, not a mere ceremonial ruler. A real ruler with real ideas. So in 1955 he shocked the world, abdicating the throne in favor of his father. He was upfront in the reasoning for such a shocking discussion. Shedding his title would in theory leave no legal barrier to his direct involvement in politics. It’s the same reason multiple British lords had renounced their own title in order to run for parliament.

But Sihanouk puts those lords to shame, by virtue of his much more senior title. Even lords bow to kings. So we can imagine how shocking it must have been for ordinary civilians in Cambodia. It was even shocking to Norodom Suramarit, Sihanouk’s father and apparent heir. He was not expecting Sihanouk to resign, and as a non royal himself, was certainly not expecting to become king on Cambodia. Yet his son did resign, and yet he was crowned. That is the unusual story of how a 60 year old man became a monarch, quite unusual for the time.

Meanwhile, Sihanouk realized the desired effect of his abdication. It was clear he would never be on equal footing with the peasant class of Cambodia, but giving up his position went a long way to convincing them he cared. That he understood their struggle and that the future of Cambodia relied on their fair treatment. He founded his own political party, vaguely big tent and fiercely monarchist. While the party welcomed people from across the political spectrum, it was in practice a right wing movement. Sihanouk was truly worried about the political climate of his country, noting a sizable shift towards leftism, and worryingly, even socialism. So he decided to lean on that favorite tool of dictators everywhere – he had the leaders of left wing parties arrested. They were thrown in jail and their followers threatened with a similar fate.

An election was held, but opposition organizations banned from holding demonstrations. Then come polling day, members of the public were openly pressured to vote for Sihanouk’s party – Sangkum – which unsurprisingly won a emphatic victory. Final results showed Sangkum winning more than 80 percent of all votes. As a result, it became the dominant party in Cambodia’s national assembly. As leader of Sangkum, Norodom Sihanouk once again became prime minister. Now in power, and without the restrictions associated with a constitutional monarch, he got to work reforming his beloved Cambodia. As is standard for newly Christians dictators, many of his initial acts were seemingly liberal. He reduced the powers of the king, believe it or not, fully embracing the concept of a constitutional monarchy. He gave women the vote, and he announced a series of programs to reduce inequality. It really seemed he was telling the truth about his motivation.

A New Political Order

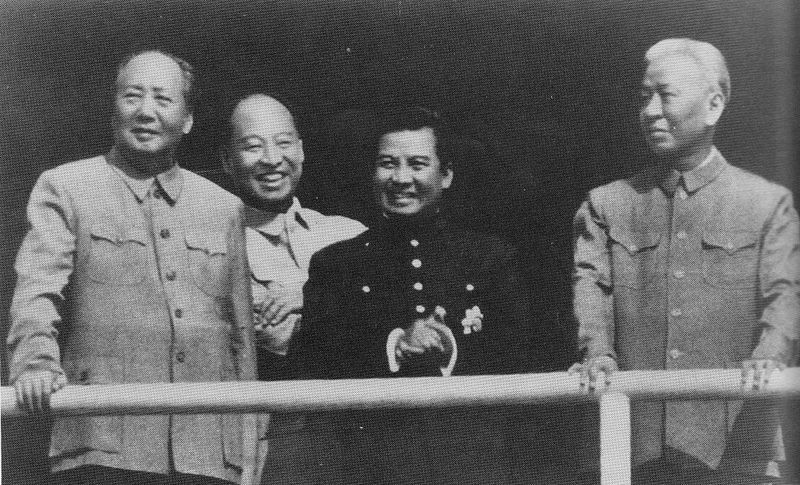

That Sihanouk was driven primarily by a desire to do good, setting him apart from so many political types. This was further illustrated when he resigned and retired from politics in 1955. Sure he returned and retired and returned again several times over the following half decade, but clearly he was not a regular prime minister. There was much instability. Sihanouk for some time had good relations with the United States, viewing it as the anti-colonial superpower of our world. But gradually he began to suspect the CIA was working against him. He came to believe they were backing rival parties within Cambodia, ultimately leading him to distance the nation from the west. China jumped at this opportunity, pulling out all the stops to secure their 1956 pact, which saw 40 million dollars in aid go to Cambodia.

But since China was still very much seen as a hostile communist power, this immediately set the narrative that Norodom Sihanouk had red sympathies. Never mind his history of hostility to communism, the capitalist west had decided to made an enemy of him, and he was all too happy to return the favor. The main opposition party, the Democrats were among the loudest voices criticizing Sihanouk’s handling of foreign policy. So in mid 1957 he called out a number of Democrat leaders for public debate. Five of them accepted. What resulted was a ridiculous television broadcast, during which Sihanouk aggressively berated the opposition. Such a tactic could easily backfire, but their inability to rebut his claims apparently led people to believe they were weak on national security. Somehow the ensuing fallout led to the demise of the Democrats, support for their party crumbling in a matter of weeks.

Thuggish soldiers and rogue police officers attacking party members did speed this along, but without a doubt their reputation was falling regardless. With the liberal opposition crushed, Sihanouk brought well known left wing activists into his Sangkum. This was the ultimate ambition of his long term political scheming, a single broad church party capable of appealing to almost all voting blocks in Cambodia. How successful this strategy could be in a true democracy is unknown, thanks to police and security forces doing all possible to ensure a Sangkum victory in the 1958 election. In fact, Sangkum won all 61 seats in the national assembly, and the opposition received less than 500 total votes. Norodom Sihanouk was now in total control of his country. But it was clear to all he was a dictator.

His plan to paint Sangkum as the party of popular consent fell flat. And as such, his reputation withered both internationally and at home. It was an environment ripe for unrest. So before the year was up, a palace coup began to unfold. It involved Norodom Sihanouk’s own interior minister, a powerful warlord, and several right wing politicians. Some might not have expected a coup from the right, but many conservatives viewed Sihanouk as a useful idiot for communism. Or at best, an unreliable ally of the right. Luckily for him, though, the plot was discovered. Swift action was taken. The interior minister swiftly arrested, swiftly executed without trial. A typical go-to move of every dictator. As the minister was the inside man, the whole plot fell apart. Sihanouk was safe – for now at least.

Also involved was the brother of South Vietnam’s president, who arranged a certain amount of support through Thailand. As such, the foiled coup came to be known as the Bangkok Plot. This only further cemented Sihanouk’s notion that the United States was out to undermine him. South Vietnam and Thailand were closely aligned to the west. They would not have made the commitment without their allies prior knowledge. And so the feeling of isolation grew – that feeling no dictator seems immune to. One year later, in early 1960, his father died. This naturally led to a succession crisis. His father was king of Cambodia, meaning Sihanouk was first in line to the throne, despite being prime minister. He had given up the throne specifically to be prime minister, and the last thing he wanted was to shackle himself with the restrictions of kingship.

So to get around this, he introduced a new position, making himself “Chief of State”, rather than king. That way he could retain the powers of a prime minister while inheriting the power of a king. Like Oliver Cromwell he had made himself pharaoh, a man above the law. As time went on Sihanouk seemed to lean more left wing, despite refusing to align Cambodia with the Soviet Union. In fat, Cambodia co-founded the Non-Alignment movement, partnering with Yugoslavia and a number of other nations wishing to stay out of te Cold War. Sihanouk believed the American government was funding a rebel force within Cambodia called Khmer Serei. While they denied doing so, it’s not an illogical move from the US, especially in those dark days of the Cold War. Norodom Sihanouk was becoming ever more left wing, outwardly at least.

The liberals recently welcomed into his party came to dominate much of it’s political agenda. He nationalized the banks and shipping. It was only natural for the west to be suspicious. But as a result of their meddling, Cambodia only strayed further from America. This culminated in a secret agreement between Cambodia and North Vietnam, America’s most staunch enemy at that time. It was 1964 and the deal provided a pathway for Chinese military aid to flow into Vietnam, first funneling it through Cambodia. Thus, laws prohibiting China from supplying the Viet Cong were sidestepped. Cambodia would keep some of such military aid, on top of receiving substantial financial support from China as a bonus. This was just the start of a series of collaborations with North Vietnam. It also marked a secret shift away from neutrality. Before long military aid from the Soviet Union made it’s way to Cambodia.

Internal Struggle

By 1966, the party had been firmly pulled to the left, and when right wing figures within Sangkum nominated a new prime minister, Sihanouk went ballistic. The new prime minister was Lon Nol, a long time ideological rival of his. So just a year later, Lon Nol resigned. And in quite the coincidence, many of the conservative politicians who nominated him were replaced by Sihanouk loyalists. It was a time of great turbulence for Cambodia, but domestically and otherwise. Relations with China were worsening. As left as Sihanouk’s government may have seemed, it was no fan of communism. So when it became clear China was attempting to spread Maoist ideas Cambodia’s significant Chinese minority, an impasse had been reached. So an unusual olive branch was offered to the United States. On hearing that Jackie Kennedy wanted to visit the historical site Angkor Wat, he personally invited her for a tour.

She accepted, and the door to diplomatic renewal was thus opened. He now claimed to have no love for Vietnam at all, or for the people on either side of the conflict. In reality he was sympathetic to the north, but what inspired such sympathy was conditional, rather than ideological. I cannot state enough that Norodom Sihanouk was no communist. He had allowed Viet Kong forces to take refuge in Cambodian jungle simply as part of the deal with China. But now they had established a foothold in Cambodia, native communist forces began to spring up. Sihanouk was genuinely worried that such forces would pull his country into the Vietnam war, or at least destabilize his rule at home. This, combined with economic stagnation and a general distrust in the establishment invoked a nightmare scenario for any dictator.

To put it bluntly, all could see Norodom Sihanouk was losing legitimacy. Desperate to appear more reasonable, he brought back Lon Nol, ideological enemy and ousted prime minister, to once again assume that role. It would prove a terrible mistake. Shock waves rattled Asia in the month of March, 1970. Norodom Sihanouk was enjoying a lengthy holiday in Europe, having left Cambodia one month before. While he lounged in luxury, his home nation descended into chaos. Mass demonstrations consumed the streets of major towns and cities, and with no clear leadership, Sihanouk’s opponents began to sharpen their knives. When the lackey caretaker brother in law Sihanouk left in charge tried to suppress dissenting politicians with force, he instead found himself arrested by troops loyal to Lon Nol. Then on the 18th the National Assembly launched a full on coup coup d’état.

Lon Nol was granted emergency powers, and Sihanouk officially deposed. So by the time the former king returned to Cambodia, he found himself on the other end of the whip. A rebel in his own kingdom. So like a true rebel, he actually established a resistance force to combat the new government. He named it the National United Front of Kampuchea, or FUNK, and aligned himself with other rebel groups. Many of which had up until that point been fighting Sihanouk, making it quite the turn around.

Most notorious were the Khmer Rouge, the group who would later commit the Cambodian Genocide. But for the time being, they were but a stepping stone on the journey to power, or so Sihanouk assumed. They had been active resistance fighters for numerous years, boating an influential network of operatives across Cambodia. This, given the fact many in Cambodia still had respect for the royal family, made it easy to whip up unrest among the populous. For the most part, Sihanouk himself was safely in Beijing, living as a stately guest. China was firmly on his side, cutting ties and undermining the new regime. Lon Nol responded by typical brutality, locking up any rebel he could get his hands on. Most assumed the government would emerge successful in the conflict – after all, almost all rebellions are doomed to fail.

But in March of 1970, North Vietnam unexpectedly launched a military offensive inside Cambodia. Said invasion threw the Cambodian populous military into disarray, giving rebels time to unify their forces. What land they captured was simply handed over to the Khmer Rouge. This did more than shift the balance of power to the broad rebel alliance, it shifted it primarily to the radical Khmer Rouge. This did, however, allow Norodom Sihanouk to visit Cambodia in relative safety, despite him being sentenced to death by Lon Nol’s regime. As time went on, Lon Nol’s position deteriorated. Rebel forces, now firmly led by the Khmer Rouge, chipped away at the stone block of statehood until it was reduced to a fine powder. Cambodia was in the grip of chaos. And so a brief flash of hope was seen in April of 1975, when the civil war finally came to an end.

Cambodian Hell

After eight hard years of struggle, the Cambodian state fell. More than 200 thousand combatants and civilians were dead, many of which at the hands of foreign invaders. But the bloodshed had only just begun, and emerging now was a dictator who made Lon Nol and Norodom Sihanouk look like a couple of school boys. Only now did they realize what a monster that man was, just in time for the Cambodian Genocide to get underway. It began immediately. As soon as Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge, residents were introduced to their new fearless leader, the infamous Pol Pot. He had the entire population rounded up and forcefully marched into the countryside. Any who resisted were shot dead, as were intellectuals. It got to the point they killed anyone they saw wearing glasses, viewing it as a sign of the bourgeoisie.

While initially an enthusiastic supporter of Pol Pot’s regime, Sihanouk was shocked by the brutality of it. Sihanouk was no angel, true, but he genuinely wished the best for his people. So to see the mass executions of innocents and forced labor camps set up by the new regime, it broke his heart. In protest, he resigned as head of state. And so Norodom Sihanouk became just another prisoner of the Khmer Rouge – better off than most considering he was under house arrest in the royal palace – but a prisoner nonetheless. Meanwhile, the Cambodian genocide was in full swing. In an attempt to turn Cambodia into a farming based socialist state, untold numbers of innocent civilians were literally worked to death. Going into 1979, more than 1.5 million people had been killed. Many simply died as a result of bad policy, but around 60 percent of the dead were executed.

Never before has the world seen a nation collapse in on itself like it did Cambodia in those dark days. There was no economy. No social fabric. Just an orgy of death. Such a crisis can only go on for so long before burning out, and burn out it did. Luckily for Sihanouk, he was kept at a safe distance. On January 6th he was sent to Beijing for safety. I’m not entirely sure why either party agreed to this. Perhaps China an incursion d Pol Pot mistakenly believed Sihanouk might eventually be of use to them. Either way, he narrowly avoided further turmoil, and Phnom Penh fell to invading Vietnamese forces the very next day.

Much like how Tanzania’s invasion of Uganda marked the end of Idi Amin’s rule, Vietnam invading Cambodia pushed out Pol Pot. Ironic, seeing that a prior Vietnamese incursion is what ushered him into power to begin with. A new regime was now set up by the occupiers. Made up of dissatisfied former allies of Pot, it was essentially a Vietnamese puppet state.

Sihanouk for one was glad. His public resignation years before then enabled him to condemn the Cambodian Genocide. This was good news for Beijing. With the new Cambodian government essentially under Vietnam’s control, China wanted influence. Sihanouk would prove to be the linchpin in their schemes. They pressured him to work with what remained of the Khmer Rouge, in order to give Cambodia the best shot at a new system. In time he gave in, taking part in negotiations overseen by the Singaporean Prime Minister. After more than a year of excruciating back and forth, an awkward settlement was reached. Along with the Khmer Rouge and several other parties, Sihanouk agreed to form a new coalition government. He became it’s official head of state, but since North Vietnam was still occupying Cambodia, it was little more than a government in exile.

And so the Cambodian Civil War stretched on. For seven long years. Then in 1989, Vietnam was successfully pressured into exiting the war. This meant exiting Cambodia entirely. It took an international coalition and a United Nations resolution, but a new transitional government was eventually set up. For his patience and shrewd deal making, Sihanouk was a key player once more. In 1991 he was selected to lead said government, but it fell at the first hurdle. The various parties involved, and especially the Khmer Rouge, could not agree on the finer details of a settlement. When push came to shove, they simply did not agree to give up their munitions. For Sihanouk this would be an unacceptable position for a new government to give up on. An armed and organized Khmer Rouge would be a constant threat, a sword of Damocles above hanging above.

In time he grew to believe the Khmer Rouge should be cut out of the process alltogether – a dengerous idea, but doable with the backing of China and Vietnam. Yet another hurdle materialized before he could though. It came in the form of some kind of medical emergency that forced him to seek treatment in Beijing. We cam’t say for certain what that emergency was, but it required six months of treatment and recovery. Only in 1993 did Norodom Sihanouk return to Cambodia, just in time for the scheduled election. On the day, it was an overwhelming victory for the coalition, which by that time was led by Sihanouk’s son Norodom Ranariddh. But the boy lacked the reputation of his more experienced father. China disapproved, and so a substitution was arranged. In June of 1993 Norodom Sihanouk once again became Cambodia’s official head of state.

A Triumphant Return

Among his first acts were a series of declarations annulling much of the actions taken since he was overthrown in the 1970 coup. The military was renamed to better match what it was before the coup, and in many ways the establishment agreed to act as if the whole thing never happened. He also appointed two prime ministers, with equal powers, and to serve at the same time. Then together they re-constituted Cambodia as a Constitutional Monarchy with limited powers.

These reforms took effects in later September, with Sihanouk again being crowned King of Cambodia. By this time he had been diagnosed with cancer, regularly having long stays in Beijing for treatment, the kind of treatment not then available in his country – even for a king. Yet Sihanok dedicated himself to being the best king possible, returning as often as possible to carry on government business. Then in 1994 something rather unexpected happened. Yet another coup d’état unfolded, this time led by one of Norodom Sihanouk’s own sons. While unsuccessful, the very fact it happened deeply affected the king. The end result was a weakening of the new political order, and the exile of a crown prince. And it would not be the last failed coup, as following years was a time of great turbulence. As should have been expected, the two prime ministers had a big falling out.

In hindsight it was only a matter of time until a feud erupted between them, and by mid 1996 they were unable to work together. Each worried the other was plotting against them, and Sihanouk threatened to abdicate if some kind of accord could not be reached. Hun Sen, one of the feuding prime ministers, objected strongly. He issued a stern warning that, if Sihanouk were to abdicate, they would change the constitution to outright disallow members of the royal family from getting involved in politics. This would effectively end the monarchy as Norodom Sihanouk saw it, reducing the king to a purely ceremonial position. It was a cynical ploy to keep Sihanouk from entering party politics, he being one of the few Cambodian political figures popular enough to take him on. And luckily for Hun Sen, it worked.

But it did little to diffuse tension in Phnom Penh, and before long, violent scenes spread though out the city. The fighting was primarily between soldiers loyal to the two main parties of government – the CPP and FUNCINPEC. Hun Sen was from the CPP, while his co-prime minister, Norodom Ranariddh, was of FUNCINPEC. I should mention at this point that Norodom Ranariddh was also the second son of Sihanouk, which goes a long way in politics. As things stood, the king would support his son no matter what. But Hun Sen was a shrewd one. As street fighting spread to other cities, it was all the pretext needed to force Ranariddh out of office. Then, with his rival banished to the political wilderness, a more passive co-prime minister was selected by the National Assembly. Sihanouk alled the shakeup an act of illegality, but the political climate had shifted.

There was nothing he could do. Going into the 1998 Cambodian election, Hun Sen’s CPP had come to dominate the government, and on the day it was widely believed the election had been rigged. Only when Sihanouk intervened did the two parties agree to accept the result and move on with the business of government. It took over a month of hard negotiation, but a much needed stability was successfully brought about. Norodom Sihanouk at this time was 76 years old, in bad health, and not getting any younger. Yet the ageing king maintained a busy schedule, often expressing a dim view on the path Cambodia was taking, when not attending ceremony after ceremony, that is. For the most part, this was the story of his final years as king. There was little he could actually do to affect the political sphere, not since Hun Sen outmaneuvered him in 1998.

By 2002, Sihanouk had decided the time had come to again abdicate, this time for good. In mid September he threatened to do so abruptly, as to immediately trigger a succession crisis. You see, in all the turmoil of the forgoing years, the rules of succession had been rather overlooked. A council was in place, whose job it would be to select a new monarch, but the details were lacking. Sihanouk wanted more clarity, but for now it was an empty threat. 2003 saw a new general election, one that blunted Hun Sen’s political might. The CCP clearly won the most seats in the National Assembly, yet fell short of having enough to form a government.

Once again the ageing king had to intervene, successfully negotiating a settlement wherein the CCP would form a minority government. But while this initially allowed Cambodia to avoid a constitutional crisis, the end result was a legislative deadlock that did little to appease either side. By early 2004 no progress had been made and Norodom Sihanouk was growing increasingly irritated, increasingly uninterested in the nitty gritty details of governance. Instead, he preferred to focus on philanthropy and raising awareness for causes he supported. He became one of the first world leaders to publicly advocate for gay marriage. And that’s just one of many issues he focused on during this period. Then in 2004 he commit the long overdue act of abdicating one last time.

During his second reign as king Norodom Sihanouk had genuinely acted in the interest of his nation. He’d worked hard to maintain a functioning and stable political system that would better provide opportunity for his deeply impoverished people. And most of all, he’d done what was needed to avoid triggering another civil war. Still, now that he was no longer the head of state he was more free to speak his mind, heavily criticizing Hun Sen and his political rivals alike. So it’s ironic that his abdication was the trigger to get the two to work together. As it stood, there was no legal provision for a monarch quitting. So when Sihanouk published an open letter announcing his decision, there was no excuse for the two parties to not come together.

As it happens, the plan worked, and on the 14th of October 2004, Sihanouk’s eldest son, Norodom Sihamoni, was chosen to succeed him. He was crowned on the 29th, leaving the old king with a well earned retirement. Sihanouk did sporadically speak out on ….. facing Cambodia – but for the most part he simply enjoyed his time as a husband and grandfather. Sihanouk also spent a great deal of time concerned with hobbies, reading books and going on boat trips. He even took up his old pastime of amateur film making, making use of his numerous homes as settings. The North Koreans had at some point built a large mansion for him, adding to the list of foreign guest residences at his disposal. On occasion, his films were entered into foreign film festivals, and eventually his entire collection would be donated to an arts college in France.

The Very End

Norodom Sihanouk made his last public appearance on the 30th of October 2011. It was the day before his 89th birthday, and fearing he was close to death, and he felt the people of Phnom Penh might wish to see him one final time. Then in early 2012, he issued a written request for how his his remains be treated and his funeral be carried out. According to it, the former king wished to be cremated and have his ashes stored in a golden urn. During all of this, he remained in Beijing, simply being too unwell to return to Cambodia. In fact, he would only actually return after his death in October of that year. A heart attack was the cause. Terrible, but not unexpected news.

Seven days of mourning was officially announced by the Cambodian government, and when Sihanouk was flown into the country, more than a million people turned out to witness it. Then after three months of being kept in the royal palace, his remains were indeed cremated. Contrary to his wishes, though, only half of his ashes were kept in the urn. The other half were poured into a river. Perhaps that’s a better way for Sihanouk to say goodbye to his people. Rivers are veins to the body of a nation. And so he will run through Cambodia’s veins forever. But what about the legacy of this man? He was, after all, just a man. But unlike others, Norodom Sihanouk holds the unique distinction of being a king turned president, turned dictator, turned king, turned private citizen. That could only happen in a country like Cambodia.

And Cambodia today is divided on how to view him. Some believe he was a true freedom fighter. A man who just wanted to do right by his people, hence his refusal to dignify the actions of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. Yet to others he was a brutal tyrant who alone is responsible for decades of chaos and suffering. Either way, he will go down in history as one of the most influential Asian dictators of all time.