To answer that question we must first take a look at Liberia itself, one of the most interesting countries in the world. Unique among African nations, it was never taken over by European empires. Escaping this fate, American abolitionists took interest in the area during the 1800s. In their view Africans might never achieve true freedom in the United States. So a movement began with the goal of repatriating freed black people within America to what is now Liberia. Of their own free will, American blacks were sent back to Africa where they established their own colony. Not exactly American, this new colony was not part of some kind of white American empire. It was independent, founded for and run by Africans. But they were not like other Africans, being raised on and accustomed to American ideals.

They saw themselves as separate from the natives who already called their new home home. Often with better access to education and business opportunity, the American Africans emerged as an elite class within their new lands, with all others falling behind. Before the outbreak of the US Civil War, more than 18 thousand free blacks relocated to what is now Liberia. Many died, but those who survived would play a vital role in the development of a their new country. In 1847 Liberia was declared an independent state, and one year later a wealthy freedman from Virginia elected it’s first president. America initially refused to recognize Liberia but the British did, effectively guaranteeing it’s security.

Ironically the American Africans saw themselves as superior to native Africans, often banning them from jobs and positions that could grant access to higher society. In fact, many native Africans were forced to work in plantations as virtual slaves, in a perverse mirror image of American slavery. Not until the year 1980 would a native African become leader of Liberia, roughly one and a half century since it’s creation. That native African leader was Samuel Doe, member of a rural tribe who until that point had little influence.

The Rise of A Killer

Born in a small rural village, Samuel Doe was a boy of little means who grew into a man of little means. Growing up in the era of decolonization, Doe like many young Africans found opportunity in military service. For ten long years he was dedicated entirely to serving in the Liberian army, eventually reaching the rank of Master Sergeant, making him a non-commissioned officer. With the coming political instability and civil strife that would soon bring Liberia to it’s knees, military experience would prove to be invaluable. Just months after being made Master Sergeant, Samuel Doe himself led a military overthrow of the government, commanding a large group of soldiers from the same ethnic group as him.

At the time conflict between the Americo-Liberians and Africans had reached an all time high, with more calling for reform each day. Responding the the tension, President Tolbert did make some attempt at liberal reform. But the changes he made were simply not enough, overshadowed by his corruption and nepotism, and by the economic disparity which grew greater by the day. As Tolbert grew more unpopular riots broke out, supported by opposition parties. Knowing this was the moment to strike, Doe and his band of soldiers killed president Tolbert, storming his home in early 1980. In the immediate aftermath they put most members of the Tolbert government on trial.

Almost all were arrested. Many of his family members were also killed or put on trial. By this time few such hatred had been fostered against the government that few felt any empathy for the government ministers – even as they were executed in public. Promoting himself to the rank of general, Doe got to work establishing a new government, with his group of co-conspirators comprising it’s cabinet. But immediately they faced a slew of problems. This group of soldiers has little political experience and were simply not prepared to govern an entire country.

The economy was in shambles, no one knew how long the new regime would last, and in short time a series of attempted counter coups were launched. Still, people were largely forgiving of all this early chaos. For many it was enough that Samuel Doe was a native Liberian for them to forgive his numerous flaws. Yet even he understood this ethnic understanding would only stretch so far. And so vocal critics began to be arrested and in many cases executed. It did not take long for the intellectual and political class of Liberia to get the message. Few were brave enough to speak out from then on. Unofficial newspapers were forced to close, and unapproved political activity was heavily suppressed.

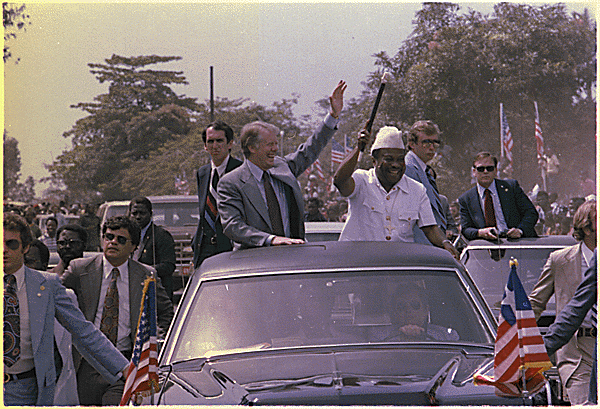

The military regime also mistreated members of certain ethnic groups, believing some to be more prone to rebellion than others. This in time would backfire massively, sparking armed uprisings in multiple regions of the country. So to counteract some of the controversy Doe attempted to legitimize his rule. First he began building a classic cult of personality, with state media outlets presenting him as the savoir of Liberia, ushering the nation into a new era of freedom and openness. In reality quite the opposite was true. He was referred to as Dr. Doe, despite not actually being a doctor. A university did grant him an honorary doctorate but that alone is usually not seen as enough for a person to refer to themselves as a doctor. In time Doe also presented him as an elected ruler, rather than a military dictator.

1984 saw the new government introduce a new constitution to Liberia. Said constitution legitimized the powers Doe had assumed. It also defined Liberia as a presidential republic with multiple political parties. That may sound like a step in the right direction but the only parties that were allowed to operate on any level were ones approved by the military government. So in effect the constitution changed nothing but for adding the appearance of legitimacy. Then in 1985 they staged a Presidential election. Amazingly, the other candidate running in the election was also called Doe. Jackson Doe apparently won 24.6 percent of the vote, far less than Samuel Doe’s 50.95 percent. This gave the latter Doe a comfortable victory.

It also gave his political party, the NDPL, a large majority of seats in the Liberian legislature. But even before the day was over international observers claimed the election was rigged and voters intimidated into voting a certain way. Corruption was certainly commonplace during the election and rigging it would be in line with other African dictators of the time. What’s more, it was claimed by observers that Jackson Doe was actually the winner. That a large number of votes for him were simply recorded as though they were for the other Doe. In any event, the opposition party refused to take up what seats they had won in congress after the election was over. After the dust had settled it turned out the vote counters had been specially picked by Samuel Doe himself and were almost certainly loyal to him above all others.

This was a common practice among the more corrupt nations of the world. Sadly it was nothing out of the ordinary, and Samuel Doe was allowed to remain in power. Doe was a capitalist and ally of the west. Western powers were therefore willing to work with him out of fear Liberia could become a Soviet ally if he were forced out of power. And so a blind eye was turned to the fraudulent activities carried out on his behalf, and on behalf of his government. This message was heard loud and clear by Doe and in the aftermath of the 1985 election, being much harsher on political dissidents than he previously had been. Ethnic violence too increased across Liberia.

The Carving of Liberia

The Dan and Mano ethnic groups were specifically targeted by the government, stirring up centuries of resentment in the process. Doe had no idea what kinds of forces he was unleashing by resorting to collective punishment of these groups. By 1989 these tensions had reached a boiling point. In that year a former ally of Doe returned to Liberia – having been exiled for years against his will. Furious at Samuel Doe, he saw the ethnic tensions and blatant corruption as the perfect storm. He knew this was his opportunity to take revenge and the presidency of Liberia with it. His name was Charles Taylor and for the last few years he had been a fugitive at large.

Taylor had spent his time in exile building a rebel force comprised of the very ethnic groups Doe had victimized since the election of 1985. In the initial stage of governing Liberia after the coup in which Doe seized power, Charles Taylor was among the most important government members. He was tasked with overseeing the importation of certain goods and services for the new cabinet, giving him control of a large sum of money. But according to Doe he stole around a million dollars for himself. When news of his crime broke he fled to America. This was a bad move considering the US saw Doe as an ally. Charles Taylor was swiftly arrested and sent to jail in Massachusetts. He was awaiting extradition to Liberia where Samuel Doe would certainly have dealt with him severely.

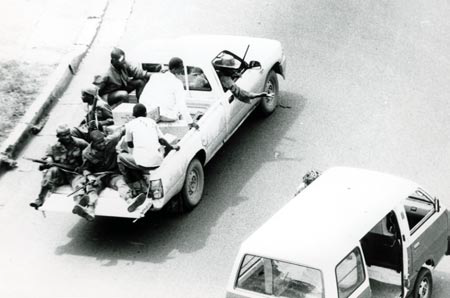

But in 1985 he actually broke out of jail and fled into the woods surrounding the jail. This daring escape is just a footnote in the story of Charles Taylor’s return to Liberia. By the time of his return to Liberia Taylor had gathered an armed force fierce enough to match his reputation as a prison breaking rebel leader. The way Samuel Doe responded to his return was exactly as he expected, sending in the army to punish entire villages and towns suspected of harboring rebels. This saw the mass killing of innocent civilians, encouraging countless more to join the rebellion. Almost immediately it erupted into a full blown civil war. So while Taylor and his forces initially faced huge resistance on entering Liberia, the population soon realized just how willing Doe was to make them a casualty of a war they had nothing to do with.

And so support flooded to the rebel side. Within a year they controlled almost all of Liberia’s land and were closing in on the capital city of Monrovia. But even as it became clear all was lost, the government continued to become increasingly brutal in their treatment of rebels, suspected or otherwise. When Monrovia finally fell to rebel forces Samuel Doe was captured and his entire guard attachment of 80 men shot dead immediately.

Unluckily for Doe he was not taken prisoner by Charles Taylor. The group who captured him were loyal to Prince Johnson, a notorious rebel leader who just recently had split from Taylor over a disagreement. Far more brutal, Doe had no idea what kind of terrible fate would befall him. While he expected imprisonment at worse and exile at best, Samuel Doe was brutally tortured to death. I won’t go into detail on his torture but it lasted for quite some time, and was even recorded on video. You can find the video freely available on the internet. But I must warn you not to watch it unless you have a strong stomach.

Life After Samuel Doe

The legacy of Samuel Doe is one of ethnic division, corruption and bloodshed. Even after his death Liberia was at war. Rebel forces continued their battles, as it was yet to be decided which group would get the all important prize of forming the next government. The brutal war went on for another 6 years, resulting in the deaths of 200 thousand people. To the amazement of many a peaceful agreement was set in place in 1997, and a democratic general election held. It saw Charles Taylor elected president.

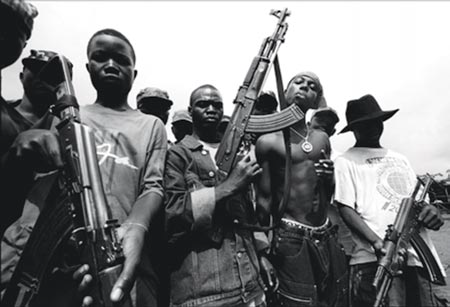

But even after the election and war was over, regional fighting flared up and the deaths continued. So as time went on the people of Liberia grew dissatisfied with Charles Taylor also. By this time the cold war was also over. The threat of communism being gone, western powers had virtually no use for a man like Taylor to be in power. In 1999 yet another civil war broke out in Liberia, a poor country that had barely began to recover from the previous war. This was was smaller but more desperate, being noted for it’s extensive use of child soldiers. The government itself relied heavily on child soldiers, often forcing them to take drugs in order to crush their disobedience. This war played out much like the one before it.

Rebels rapidly swept through Liberia and by the end of it just 20 percent of the country was under government control. Desperate not to meet an end the way Samuel Doe did, Taylor brokered a peace agreement. As part of it he resigned as president and went into exile in Nigeria. But like many former dictators Taylor found himself in a world of trouble when the government protecting him got cold feet. In 2003 the Nigerian government agreed to revoke his protection. Fearing that he would not be given a free and fair trial, it was agreed he would not actually be sent back to Liberia. On finally being found guilty of Crimes Against Humanity, Taylor was sent to prison in the United Kingdom. To this day he is imprisoned in the UK.